At a time of perceived decline in the British airshow industry, there is one area that is growing like never before. With the first evening “pyro display” bursting onto the scene in 2010, there are now at least ten on the circuit. Among those setting the furious pace of development are Guy Westgate and Rob Barsby of Aerosparx.

Since being established in 2015, Aerosparx have performed across throughout Europe, including night shows in the UK, Finland, France, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Ireland and Poland. The team has recently been as far afield as Saudi Arabia and even New Zealand. However, preparing their two Grob 109b motor gliders for a trip halfway around the globe is a technical and logistical challenge, to say the least. To find out for myself exactly what has to take place to make such an ambitious trip work, I joined the team on a bitterly cold February weekend at their base at Husbands Bosworth Airfield, Leicestershire, ahead of their trip to the Zhengzhou Airshow in China.

Arriving at the ESS Aviation Services hangar on a rain-soaked Saturday morning, photographer Alex Prins and myself sat down with Rob and Guy over a cup of tea to discuss the plan for the coming two days. Guy, a British Airways 787 pilot, is no stranger to the airshow world. He was involved in setting up the first two pyrotechnic display acts in the country – GliderFX and Twister Aerobatics – and is an eight-time unlimited level National Glider Aerobatic Champion. That does not, however, make him a so-called “avgeek”, and he openly joked that his aircraft recognition skills are egregiously sub-par for an airline pilot.

Guy explained: “My first pyro display was at an event called ‘Odyssey’ in West Sussex. It was such an experience. Nobody had fired waterfall pyro from a glider before, and I didn’t really know what to expect. I had my heart in my mouth, but the effect was just magical. I was totally wonder struck! The display director was my friend and the chief pilot for Rolls Royce, Phill Odell. We both knew that night that we had seen the start of something very special.

“That display was spotted by Mike Miller-Smith of Aerobility – the, UK’s premier disabled flying charity – who asked me to help with a night display that opened the London 2012 Paralympic Games. The process of certification for the Tecnam for that flight over London lead to techniques, the permit process and much of the knowledge that we have today.”

While Guy has been with Aerosparx since its inception, Rob joined the team at the start of 2017. In his day job, Rob is as the creative director of a marketing agency, Shinx Creative, who are involved in several projects with national aviation organisations to encourage youth engagement and develop skills across the aerospace sector. One project Rob has developed involves revolutionary 360-degree video camera live-streaming the 360 videos direct to event media and smartphone apps during air displays.

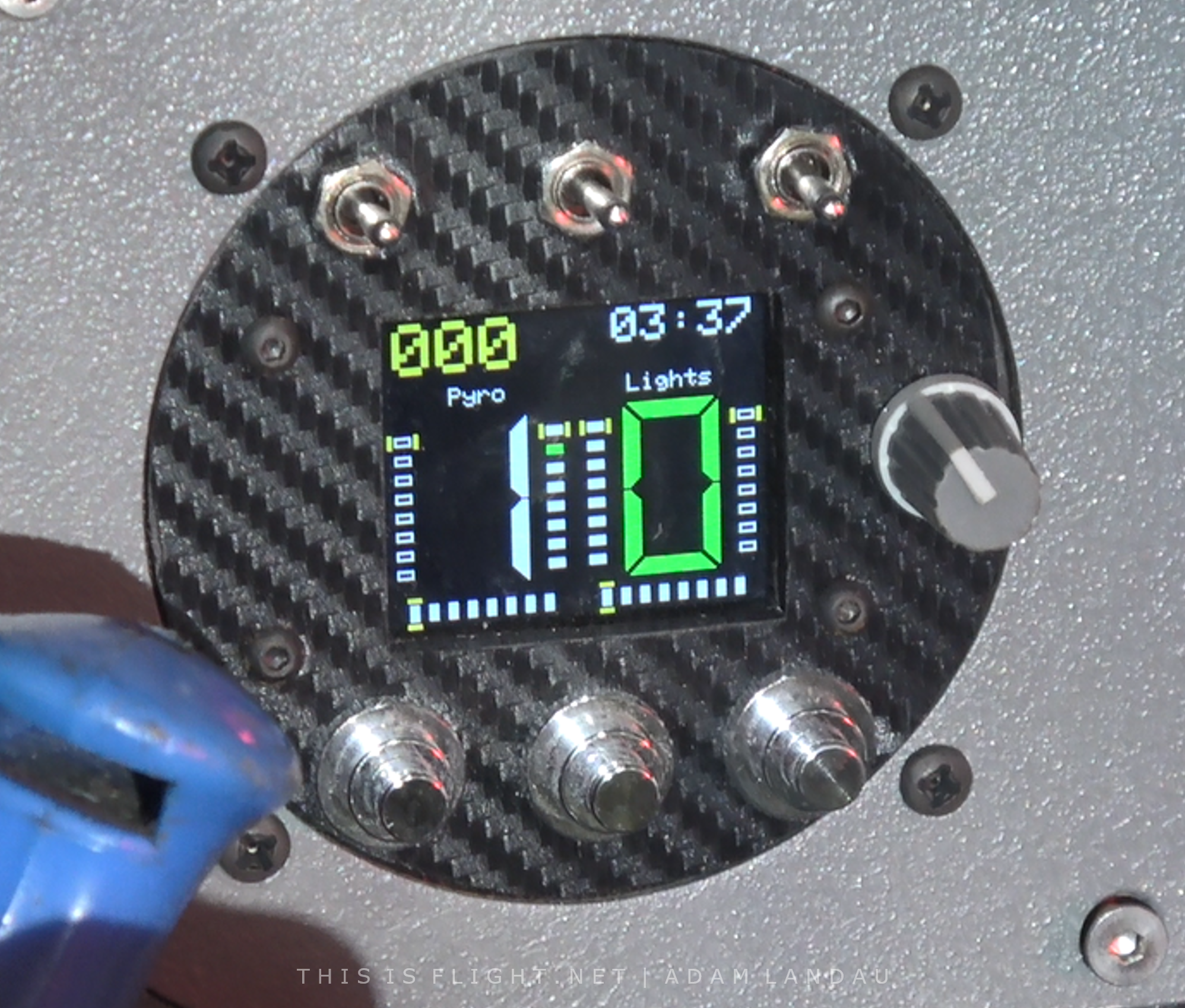

By the time of my arrival, the pair had already been working at the airfield for two days. Rob’s aircraft was outside on the tarmac, almost ready to fly, while Guy’s plane remained in the hangar, its cockpit a tangled mass of wiring and parts. Both were working on installing a new computer, designed by Simon Wood, to control the pyrotechnics and LEDs. The wired connections to the pyros and lights needed to be built almost from scratch and fixed under the seats, which was an inevitably lengthy and delicate operation.

The new computer is a safer and more precise means of firing the over 3,000 pyros which can be jettisoned from each aircraft. “Safety is very important to us”, explained Guy. “It’s actually very hard to fire the pyro; we’ve got three interlocks now before we can actually get a fire signal to the pyro.”

The new computer’s user interface is surprisingly intuitive, the large digit on the left denoting which ever pyro sequence is currently selected and a column of boxes clearly showing the state of each pyro firing squib.

“An open box tells me that the main computer has no ‘handshake’ with that particular pyro control box. The wing, spats and the trailing edge boxes change to solid white to show that everything is booted up and working. It [the white box] goes green when it detects a squib, and red when its fired,” Guy informs me. When Guy selects a pyro sequence with a green box, arms the pyro system and presses the ‘fire’ button, the computer directs an electric charge to the designated squib, thus igniting the pyro attached to it. For the next five seconds, the system locks out the fire button to avoid a cold or distracted pilot accidentally firing two sequence steps simultaneously.

In addition to changing the method for firing the pyrotechnics, they have also upped the quantity enormously. With pyro stations on the wingtips, wheel spats and trailing edge, Guy now believes his team can carry three to four times more pyro per aircraft than any other airshow performer. As well as adding to the visual spectacle, this also allows for a much longer display. “We can fire up to eight minutes of pyro now, if we chose to do that,” he added.

Rob, meanwhile, was working on the brightly-coloured LED strips which adorn the sides of the aircraft. Ensuring the strips were accurately positioned, he then worked his way along them with clear tape and a hot air gun, which would shrink the tape tightly around the light strips. “We’ve found that the silicon that goes over these LED strips can yellow quite quickly – in UV light, I’m guessing”, said Guy. “So Rob’s applying a protective UV cover, which will not only waterproof them better, but also hopefully block out some of the UV light, which will keep them white for longer.”

The new computer has also allowed for the development of much more engaging patterns for the LED strips. Among the two favourites were the vibrant and colourful ‘rainbow’ and the mesmerising ‘flame’, although there was talk of further tweaking both of these before the show season begins.

While the lights and cockpit were eventually completed by the end of the day, work continued until after midnight, quashing plans to test-fly both planes that evening. Pilot magazine photographer Keith Wilson therefore seemed somewhat surprised the next morning to see that one aircraft was still missing its wings and tailplane, when he arrived for his air-to-air photo shoot. However, like any glider, the Grob can be rigged in minutes, and the plane was soon rolled out of the hangar shortly after 11 o’clock and readied for flight.

It was another icy day, with a biting wind that threatened to cancel any aerial activities, although the report from the photo plane was that it was reasonably smooth above 4,000 feet. The briefing for the air-to-air took place in the gliding club café over lunch. Nothing was left to chance and every aspect was discussed thoroughly and confirmed by all parties. Given the Grobs’ cruising speed of around 85-90 knots, which would push the Cessna 172 camera ship to the limits of its slow speed performance, it was vital to have a simple and comprehensive plan for the join-up and photo shoot.

Radio communications were another topic requiring careful consideration. Given that the formation element of the flight would essentially be series of gentle turns, the team’s usual display radio calls often would not apply. Instead, new commands were formulated, with much care taken to ensure similar messages had differing numbers of syllables to avoid confusion, such as “smoke – on – go… smoke-off” and “in–crease-bank… less-bank” – both three and two syllables respectively.

A brief hailstorm caused a short delay to proceedings as it passed over the airfield, but the flight was, ultimately, a success. Upon its completion, the two Grobs broke away to perform some individual aerobatics.

I, meanwhile, was in the back seat of the Cessna, wearing five layers of clothing to protect myself from the gale howling through the open front window. It was my first air-to-air experience, and Keith had told me that, taking wind chill into account, the temperature in the back would be almost -20°C for the flight’s 55-minute duration. For the first time all weekend, the weather back on the ground seemed almost palatable in comparison.

As darkness fell, it was all hands on deck as preparations were made for the evening’s flight. Even though we had almost 90 minutes before we needed to be in the air, this was barely enough time to fuse and fit the aircraft with their moderate pyro load, working in subzero temperatures and a biting wind.

Guy and Alex then drove off to position battery-powered lamps along a length of the perimeter track, which was to be used as the runway. The lamps served as makeshift landing lights and were surprisingly visible from the air.

After another briefing beside the aircraft, we re-launched for the second flight of the day. This was just as much a chance to test the new pyro systems as anything else, with Guy firing three sequences of Waterfall and two of Roman Candle effects from his wingtips and wheel spats.

Our antics caught quite some attention on the ground, with reports from the public of a burning plane streaking across the sky. The emergency services were quickly stood down, but the press soon picked up the story, with the online papers reporting on the flight the following day.

Guy explained: “The safety services are in a cleft stick, as even when they have advance notice of displays and pyro practice flights, somebody will always call ‘999’, and then they cannot ignore a report of an aircraft in distress, just in case it really is in trouble!

“All we can do is thank the people who had called ‘999’ for their responsible actions.”

Pyro displays are neither cheap nor easy, and in their struggle to improve, Guy commented that a small increase in output required a disproportionately bigger increase in effort. After just two days with the team, each time working beyond midnight, I can certainly believe that to be true.

In the days following my visit, both planes were packed into their shipping container and, at the time of writing, are heading to China by sea. At the end of April, they will perform at the Zhengzhou Airshow in Henan province, along with other teams from the UK, Italy, Lithuania and the USA. Then, and only then, will it become clear if the hundreds of hours of work invested by Rob and Guy throughout the winter has paid off.

Follow the team’s trip to Zhengzhou in part 2, which will be published this May, and in our documentary, Sparks will Fly: the Night Air Display Revolution, which will be released later this summer.

Adam Landau is a journalism student, lifelong aviation enthusiast and the founder and editor of This is Flight. Photos come from Alex Prins, with additional contributions from Guy Westgate and Keith Wilson of SFB Photography. We would like to thank Rob, Guy and everyone else who made this article possible.