THE SKY AT NIGHT: AIRSHOWS RE-IMAGINED

THE SKY AT NIGHT: AIRSHOWS RE-IMAGINED

WORDS BY ADAM LANDAU | PHOTOS BY ALEX PRINS

At a time of perceived decline in the British airshow industry, there is one area that is growing like never before. With the first evening “pyro display” bursting onto the scene in 2010, there are now at least ten such shows on the circuit, and almost as many display teams developing firework-filled performances to fly at them.

The phenomenon began in 2010 with Guy Westgate’s glider display team, GliderFX. “My first pyro display was at an event called ‘Odyssey’ in West Sussex,” Guy said. “It was such an experience. Nobody had fired waterfall pyro from a glider before, and I didn’t really know what to expect. I had my heart in my mouth, but the effect was just magical. I was totally wonder struck! The display director was my friend and the chief pilot for Rolls Royce, Phill Odell. We both knew that night that we had seen the start of something very special.”

The same year, the Twister Duo, with whom Guy also flew, performed their first pyrotechnic display. They were quickly followed by Brendan O’Brien and his flying circus, and the idea gained yet more traction in 2012 when the Aerobility charity organised a pyrotechnic display for the opening ceremony of the Paralympic Games in London – a display which, Guy said, lead to many of the techniques, processes and knowledge that the industry relies on today.

However, the night show concept became popular in North America long before it crossed the Atlantic. The idea was popularised in the early 1990s, when airshow pilots like Bill Leff were experimenting with fixing basic pyrotechnics to their wingtips.

“A handful of civilian air show pilots began using roadside fireworks as part of their routines,” explained Luke Carrico, full-time airshow director and narrator, and ground crew with the Twin Tigers aerobatic team. “Here in the US, often at state lines on the interstate highways, there are giant warehouses full of fireworks open all year round. It’s sort of odd as I come to actually think about it. A cluster of Roman candles for example could be attached to the wingtips of an aircraft and be wired to ignite upon a flip of switch, similar to turning on the wingtip strobe lights.”

The method for attaching the pyrotechnic effects themselves is surprisingly rudimentary. In most cases, aircraft are simply modified to carry metal struts and attachments on the wingtips and wheel spats. The pyrotechnics themselves come packaged in cardboard boxes and tubes, which are clasped or otherwise fixed into these attachments before the entire complication is bundled together with a combination of sticky tape, zip ties and Jubilee Clips.

Indeed, this kind of system is still widely in use today and has barely changed since the days of old – except the quantity of pyrotechnics used has increased many times over. In most cases, the pyrotechnics themselves are ignited electronically by a simple switch in the cockpit. This sends a small electric charge around a circuit, to which the pyrotechnics are connected via an electronic detonator.

In the UK, Brendan O’Brien uses exactly this system for his “Skygasm” routine – a four-minute pyrotechnic spectacular in his Schweizer 300 helicopter. The charismatic 70-year-old flies with a small control box strapped to his knee, which allows him to select one of four circuits, each wired to a different selection of pyrotechnic effects.

“It’s effective,” he confided, laughing. “I mean, it’d be a bit tricky sticking your hand out the door with a match!”

Technology has developed hugely since those early days, and several teams recently developed highly advanced computer software to control both their pyrotechnic systems and LED lights.

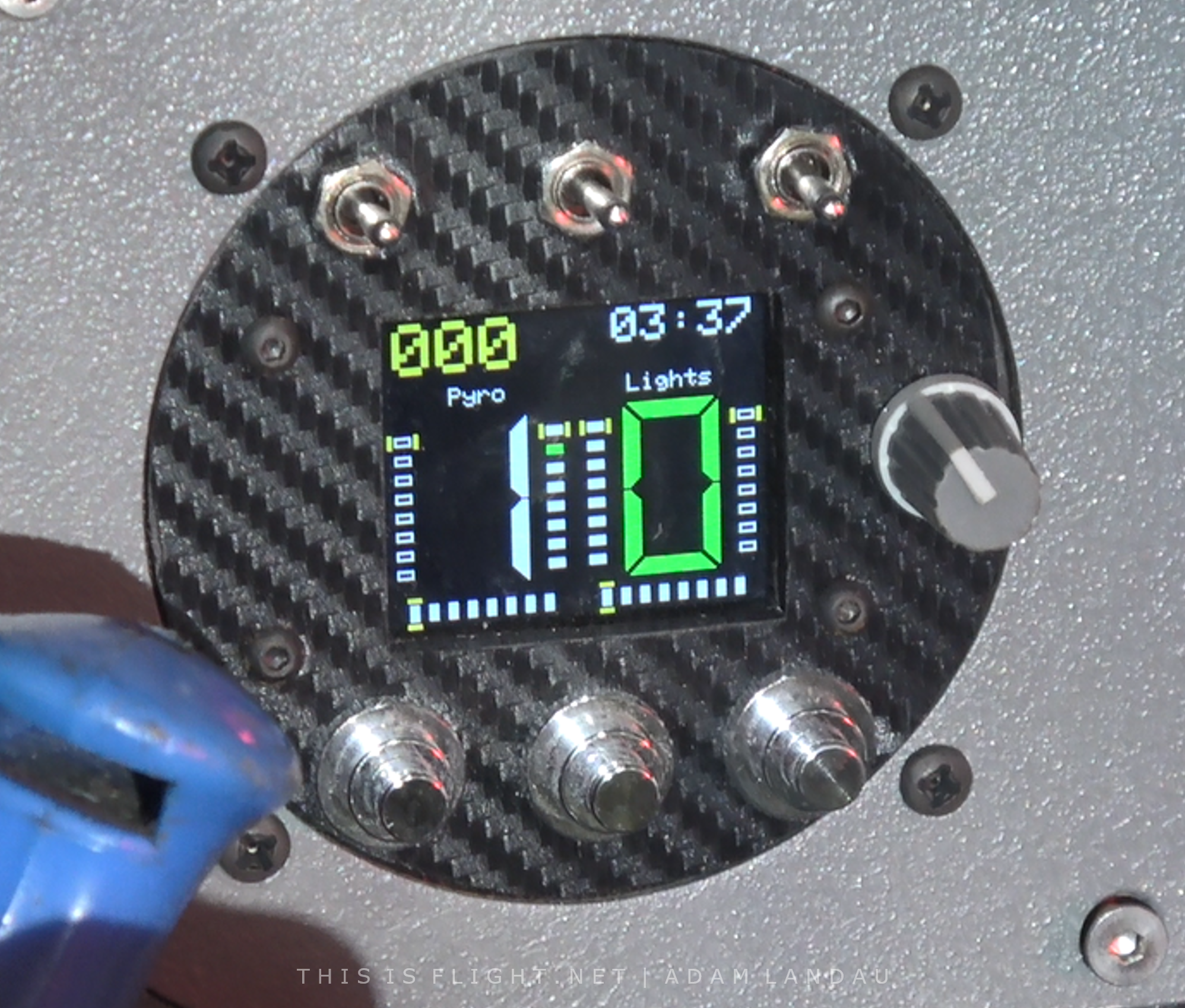

Guy Westgate’s latest team, Aerosparx, use a highly complex (and very expensive) computer system developed especially for the team by 2429Technologies, which gives the team eight separate firing solutions per aircraft as well as eight bespoke LED patterns. The new computer’s user interface is surprisingly intuitive, the large digit on the left denoting which pyro sequence is currently selected, surrounded by columns of boxes clearly showing the state of each of the firing solutions.

“An open box tells me that the main computer has no ‘handshake’ with that particular pyro control box. The wing, spats and the trailing edge boxes change to solid white to show that everything is booted up and working. It [the white box] goes green when it detects a squib, and red when it’s fired,” Guy explains. When he selects a pyro sequence with a green box, arms the pyro system and presses the ‘fire’ button, the computer directs an electric charge to one of the eight sets of firing solutions (as denoted by the large number on the left), thus setting off any pyrotechnics wired to it. For the next five seconds, the system locks out the fire button to avoid a cold or distracted pilot accidentally firing two sequence steps simultaneously.

The computer also introduced additional failsafe measures to make sure pyrotechnics cannot be fired either by mistake, or because of a technical fault. “Safety is really important to us,” Guy says. “We now have three interlocks on the computer’s pyro firing circuitry, so it’s actually quite hard to fire the pyro. When the computer turns on, it fails safe, so we actually have to jog it on to the first pyro solution before we can fire it.”

One of the biggest obstacles for pilots developing their pyro displays is not the quantity of pyrotechnic they can carry, but the duration of each effect, which is typically just 30 seconds to a minute. With their eight firing solutions, up from four with their old system, Aerosparx are able to display much longer than many other teams, with pyrotechnics firing non-stop for a full eight minutes. “To get a better pyro display, I think you’ve got two options,” said Guy. “You can either have more pyro, fire them smarter, or perhaps do both. We’ve decided to do both. We really can be much more flexible with our pyro.”

Brendan, however, remains a sceptic: “You can have all sorts of electronic wizardry, and the more you have, the more likely it is to fail. We apply the KISS principle. Keep It Simple, Stupid.”

But as Luke Carrico explains, there is more to night air displays than just pyrotechnics. “We’re seeing more performers use LED lights on their aircraft, often with colour changing capabilities and featuring the ability to sync with music, improving the entertainment value,” he says.

With all these new developments, airshow announcers like Luke are all too keenly aware of the differences between night air displays and traditional airshows. “As an announcer, I have found that night show performances are more focused on the production of the display and generally have less narration as the music does the talking. There is often a storyline associated and while the displays themselves are almost always visually impressive, without a decent sound system the story can quickly become lost.

“There seems to be a higher production quality in night show performance, and there should be. The open night sky combined with the carnival like atmosphere of an airshow creates a very unique environment. It is often cooler and more comfortable in temperature and even the airport’s runway lights go into play for the overall ambiance. All of this combined creates what I like to call the ‘Disney Factor’. It’s the sights, the smells, the sounds, and most importantly, the story.”

Despite being the birthplace of pyro displays, with far more night-capable performers than any other nation, Luke says that in the United States, demand for night airshow acts is already starting to outstrip supply. “As an airshow director, I can tell you with certainty there is a considerable lack of night qualified airshow pilots and it can become difficult to book enough for a well-rounded night show, especially when there are other shows scheduled elsewhere on your given weekend. I think a quick way to great success in the North American airshow business, as it pertains to aerial performers, is to fly something unique and different – and have a night show.”

In the UK, meanwhile, a lack of pyro-capable acts is less of a problem. Public night airshows in their truest form are not permitted, and instead, aircraft must complete their display before night officially begins, 30 minutes after sunset. In the long summer evenings, the sky can still be quite bright by this time, making the window when pyro shows can take place very short – typically just long enough for a couple of acts. This means that each individual show must be much smaller, and the ten or so pyro-capable acts could hypothetically be spread across two or three events on the same day. Even with the sector’s recent growth, this is still a rare occurance.

The ‘Sunset Plus 30’ rule is particularly problematic at seaside shows, as some light aircraft are not allowed to fly at night at all. This means they must not only complete their display, but also transit back to a suitable airfield and land within half an hour of sunset. When there is a quarter-hour transit flight from the airshow venue to the nearest airfield, that pushes the display times forward, and means the sky is even brighter during the performance.

So why is it that pyrotechnic displays are booming in the UK, despite inhospitable regulations and an airshow industry which is, generally speaking, facing terminal decline? Brendan O’Brien thinks the answer might have something to do with the Shoreham Airshow crash of 2015. Although it was the first time, in more than 60 years, that members of the public had been caught up in a British airshow accident, the disaster brought sweeping changes to the airshow rulebook, which most industry insiders agree are not intended to improve Britain’s near-impeccable safety record, but to absolve the aviation regulator of any future blame. The resulting red tape and Herculean new fees levied against airshow organisers caused a severe downturn in the industry, and brought about the end of many traditional airshows and performers.

“I think twilight pyro shows, and ultimately night pyro shows, is one of the few areas in a very beleaguered airshow industry where there is room for being entrepreneurial, being inventive, being imaginative,” Brendan explains. “It is, I say, beleaguered because as a result of an accident that happened in 2015, it’s become very difficult to do a lot of things. It is one of those areas where you have an opportunity to innovate.

“So where are airshows going? Well, I can give you some tips for the top. It may be that we shall go back to the flying circus, because it’s about all that you can do within a confined space. The bigger aircraft, like the jets, whether they will be allowed in ten years’ time to fly over land, we don’t know. I think in fact you will get an upsurge of coastal shows. I think the twilight and the night pyrotechnic shows that a few of us have been entrepreneurial about will start to develop, but you may see less and less of the bigger aircraft.”

Brendan then went on to explain one of his own innovations for the future. “I think I’d better keep my cards close to my chest here, but for those who have seen – and it did go viral – the night pyro show in Avalon in old Australia [in March 2019], it was very spectacular, and they were using lasers. And now, we, too, are looking at using lasers…”

The idea that the Shoreham Airshow crash is singularly responsible for the current changes to the UK airshow industry is only part of the story, however. Airshows are becoming less varied and less exciting for a litany of reasons, and Aerosparx’s lead pilot, Rob Barsby, argues that night displays are an integral part of combatting this.

“It’s about entertainment,” he says. “If you have a day show, that’s great, don’t get me wrong, but you’ve got an issue. If you actually look at the average person, they don’t really care about aeroplanes. The night show is more about visualisation. It looks cool, but actually the aeroplane is just a facilitator.”

This, Rob believes, is why many seaside airshows are becoming less about the flying display itself, and more about creating a broader festival at which the air display is one of several headline attractions. The Bournemouth Air Festival was one of the first in the UK to experiment with this model in 2010, by staging a mix of afternoon and twilight air displays, maritime displays, trade stands and concerts. Now, others are following suit: Sunderland, Shuttleworth, Herne Bay, Ayr, Torbay, Eastbourne and Swansea have all dabbled with night displays; the Midlands Air Festival mixed daytime and evening displays with hot air balloon launches in 2018, and there are a growing number of more generic festivals, parades, firework displays and model airshows buying into the pyrotechnic air display format, such as the MLE Firework Championships, the Go! Festival, Jersey’s Battle of Flowers and the Swanage Carnival, among many others.

Rob is a big advocate of the festival-style airshow and is keen to see this model expand further in the UK, particularly as general airshow participation has fallen from around seven million people annually in 2014 to five million just five years later. In fact, according to the British Air Display Association, airshows last year dropped behind horseracing to become only the third best-attended form of outdoor entertainment in Britain, despite generally good weather and a roughly equal number of events when compared to the previous season. Rob recognises the problem, and believes traditional airshows are a dying format. “If you actually look at the whole experience [of the festival model] from start to finish, it’s not just an airshow,” he says. “It’s a whole experience made up of multiple events with entertainment value, eating value, retail value, etcetera.”

Rob has even been critical of some night display acts for falling into the trap of making their displays too aviation-centric. “All of them are doing the same thing, aren’t they?” he muses, as he lists some of Europe’s biggest pyro-capable airshow teams. “The only thing they’re changing is the aeroplane. All they’re thinking is that their aeroplanes are different and cool, whereas actually, to the average person – the target audience – they don’t care about the aeroplanes. That’s where Aerosparx is really smart, because we actually do something different,” he said, referrencing the team’s experiments with lasers, drones and ground-based pyrotechnics. “They’re about aeroplanes and fireworks. We’re all about pushing that boundary and reinventing the wheel.”

The idea of airshows becoming less aviation-centric is a nightmarish thought for some aviation fans, but the figures tell a clear story, and a certain amount of evolution is clearly required for the industry to survive. With most European air arms now underfunded and overcommitted, and classic jet operators increasingly deciding to shut up shop, the days of sensationally-powerful jets screaching across the sky all day long are long gone, and as far as the general public are concerned, only two or three of the traditional crowd-pullers survive on the British airshow circuit today. With pyrotechnic displays capturing the public imagination of late, and the festival format encroaching on ever more aviation events (even at the bastion of avgeekery that is the Royal International Air Tattoo), it may simply be that this is the best, and only, way forward. After all, the entrepreneurial spirit and entertainment value that night airshows can offer is surely what the airshow industry has always been all about.